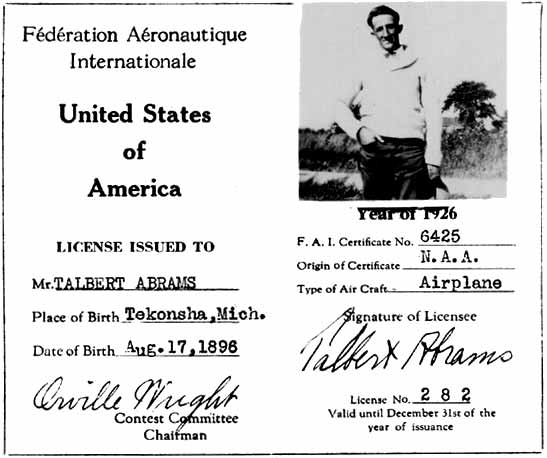

Ted Abrams , 1895-1990, was a living legend. His aviation accomplishments spanned seven decades as an inventor, explorer, and business executive. He has enough firsts to fill a book. A point of interest: his pilots license was signed by Orville Wright. He was there when barn stormers and wing walkers were popular, and he was there when American astronauts landed on the moon. An international celebrity, known for his creativity, Ted had a God given talent which allowed him to predict scientific advances which always turned out to be accurate.

Ted Abrams , 1895-1990, was a living legend. His aviation accomplishments spanned seven decades as an inventor, explorer, and business executive. He has enough firsts to fill a book. A point of interest: his pilots license was signed by Orville Wright. He was there when barn stormers and wing walkers were popular, and he was there when American astronauts landed on the moon. An international celebrity, known for his creativity, Ted had a God given talent which allowed him to predict scientific advances which always turned out to be accurate.

Ted Abrams remembered very clearly in 1903, when he was only eight years old, an event which sparked the young farm boy’s dreams. He lived on a farm in Tekonsha, Michigan. One day when he came home his father excitedly told him “those Wright boys have flown an airplane”. Ted’s dream of flying continued for years before he was able to actually become a part of aviation. He got a job at the Glenn Curtis factory in Buffalo, New York. Glen Curtis along with the Wright brothers was recognized as an early pioneer in aviation. Ted was not catapulted immediately into notoriety, he started out grinding valves and worked as a helper in the drafting room. This simple beginning did not slow his burning desire to succeed in aviation, he was content at least to be working on aircraft.

Ted, ever anxious to become more involved in aviation, joined the U.S. Marine Aviation Section. On his first flight he realized that flying was in his blood, and this was the fulfillment of his fondest dream. He was stationed at the Marine base in Pensacola, Florida, and soloed in 1918. He was scheduled to regularly fly missions throughout the Caribbean, and served with the Corp. until 1919, taking aerial photographs from the cockpit.

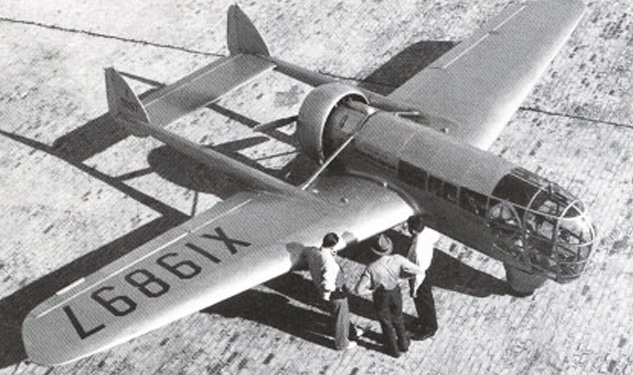

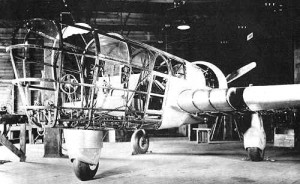

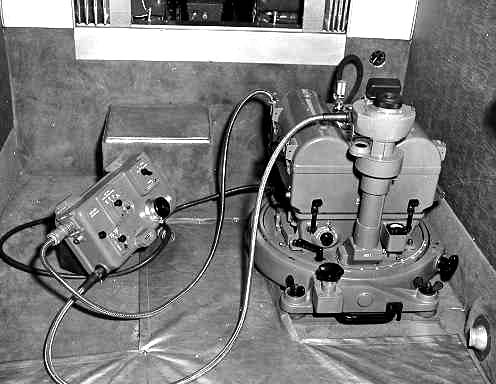

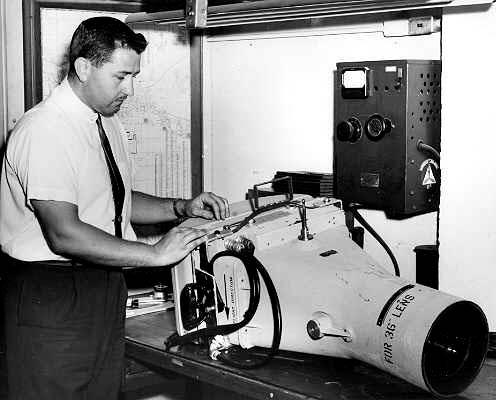

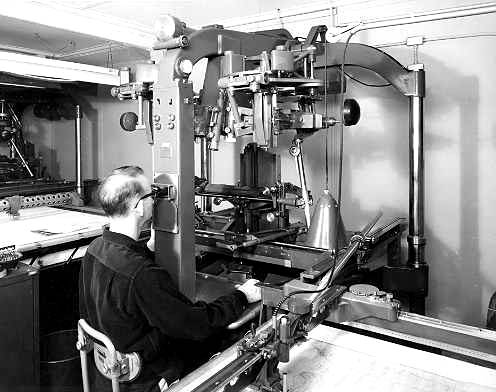

He renamed the company Abrams Aerial Survey Corporation, and after several lean years finally established itself as a first class entry into the new world of aerial mapping. Using stereoplotters his company began producing maps which could be used for highway design and construction projects. His successful mapping of a difficult highway route which was the proposed U.S. 27 gave his company the distinction of developing highway engineering. His company expanded, and through the 30’s he was awarded government contracts, and the future appeared prosperous.Ted was never satisfied with modifying conventional planes to accommodate the aerial cameras, so in 1937 he designed a revolutionary plane with a huge glass nose, twin tail booms, a pusher engine, and a tricycle landing gear.

The plane was built in Marshall, Michigan, and Ted fondly named it “The Explorer”. When the Explorer’s useful life came to an end in 1948, it was donated to the Smithsonian. It sat unceremoniously in a warehouse until 1975, when it was returned to Lansing for restoration. The revolutionary Explorer was the first aircraft designed exclusively for aerial photography. When it arrived back in Lansing it was a nostalgic moment when Ted Abrams, then 79, inspected his creation, remembering when the now rusted craft was at one time a shiny reality of his dreams. Lansing Community College students started on the restoration. I was told that all the glass was broken, that when the plane was built tempered glass was not available. All the glass needed replacing. Unfortunately the restoration could not be completed by the students, and in 1981 it was returned to the Garber Facility where it awaits an uncertain fate.In 1938 Ted established the Abrams Instrument Corporation. The company manufactured camera parts for the government, intervalometers,

And many other parts needed for his many numerous contracts. The Instrument Corporation was started at a very good time with WWII approaching. During the war it produced camera assemblies for reconnaissance. Ted also conducted a complete training center, The Abrams School Of Aerial Surveying and Photo Interpretation for the U.S. Marine Corp. He was acknowledged as an advisor to the military. So both companies prospered during the war mainly due to the Government contracts.

After the war Abrams Aerial Survey Corporation became one of the nations largest and busiest. The ever busy Ted was involved in assignments which took him to 96 countries and made seven around the world trips in the 50’s and 60’s. The Tekonsha farm boy was finally receiving richly deserved recognition. For his participation in “Operation Deep Freeze” at the South Pole in the 60’s he became one of the few persons in the world to have a mountain named for him, besides being awarded the Antarctic Service Medal. On Oct. 10, 1959, he boarded a Pan Am airliner and flew around the world in 42 hours and 26 minutes, a new speed record. This was his third round the world flight.

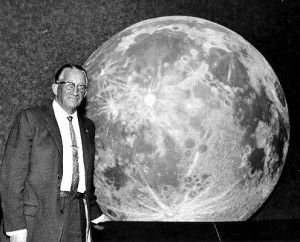

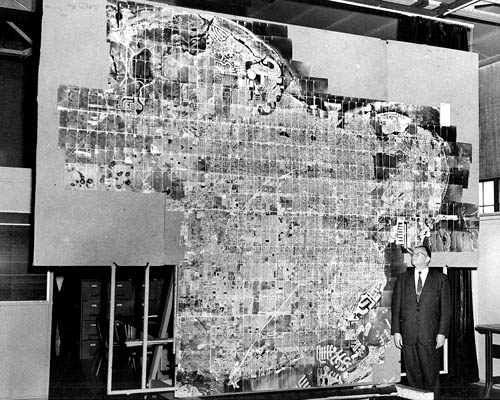

Beginning in 1945 Ted funded the Talbert Abrams Award for gifted students in science education. He also set up engineering scholarships through various engineering societies. Michigan State University had for years promoted a project to build a modern planetarium on the campus. In 1961 it became obvious that contributions were not going to cover the construction cost. Then Talbert Abrams, through the Talbert and Leota Abrams Foundation contributed the remaining $250,000 needed to build “One of the finest facilities of it’s kind in the world”. This was just another indication of his generosity toward his community. Michigan State University directed that the new facility be named The Talbert and Leota Abrams Planetarium. In 1998 the Foundation presented the Library of Michigan Foundation a check for $100,000 to purchase new materials for their genealogy collection. This gift brought the total contributions of the Abrams Foundation to $855,540 over the past ten years. Ted continued to receive impressive honors for his community service and generosity. One such honor was a tribute from the Michigan Senate for his “outstanding service in the field of aerial surveying”. He was presented honorary doctorates from three Universities. He was the first individual inducted into the Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame. In 1973 he was installed into the OX-5 Hall of Fame, along with Jimmy Doolittle, Eddie Rickenbacker, Admiral Byrd, and Amelia Earhart. Ted was on the first scheduled flight to Moscow after WWII. He made the trip twice.Abrams flight time is unlikely to be challenged. In one of his many testimonials he noted that he had “mapped 1,720 American cities, 515 counties, 5,800 miles of highways, 48,000 miles of utility lines, plus more than 1,000 major projects in 96 countries.

Ted Abrams Admires Mapping Job Flown by Wayland Mayo and Grant Kettles.

ST. Petersburgh, Florida. 21 Flight Lines, Over 700 Photos. Photo Credit to Wayland Mayo